Home Safety For Seniors Checklist

If you are looking for a complete home safety checklist for your senior loved one(s), then follow our guide below!

Home Safety Checklist For Seniors

A home safety assessment offers a unique way to proactively assess your home’s safety. This assessment can help seniors who live independently or have an older home with potential dangers. Check out the CDC’s guidelines here for more information.

A home safety checklist needs to include the following items:

Floor Safety

❒ Keep paths free of any furniture in each room of the house.

❒ Secure all throw rugs with double-sided tape or nonslip backing.

❒ Make sure there are no other objects, such as papers, boxes, shoes or blankets on the floors.

❒ Keep all wires securely taped or coiled next to walls.

Kitchen Safety

❒ Keep most frequently used items on the lower shelves.

❒ Have a sturdy step stool in the kitchen, if needed.

Bedroom Safety

❒ Tub and/or shower floors should have nonstick rubber mats.

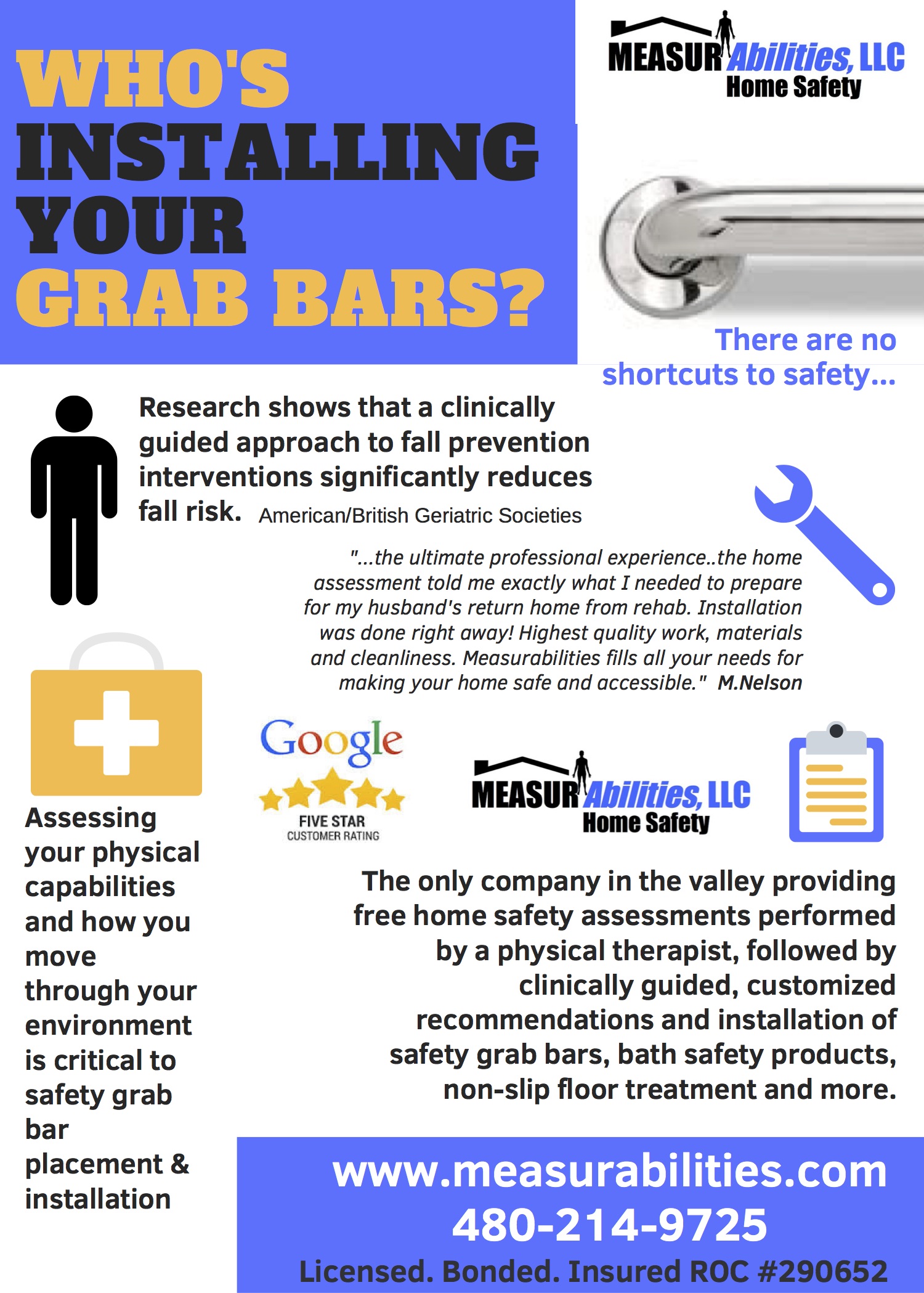

❒ Have grab bars to use for getting in and out of the tub.

❒ Grab bars can be placed around the toilet, as well.

Bathroom Safety

❒ Light(s) should be near the bed within reach.

❒ Light the path from the bed to the bathroom well with nightlights.

Stair Safety

❒ Remove any loose objects from the stairs/steps.

❒ Fix any broken or uneven steps.

❒ Make sure there is no loose or torn carpeting in the area.

❒ Have sufficient lighting above the stairways.

❒ Make sure there is a light switch at the bottom and top of the staircase.

❒ Have handrails on both sides, making sure they are not loose or broken.

❒ Handrails should run the full length of the stairway.

Other Home Hazards

Pests and chemical hazards always pose a threat to homeowners. Use these safety tips:

❒ Test for radon and lead. Homes built before 1978 tend to contain lead in their paint, pipes and soil.

❒ Check for mold/mildew.

❒ Seal up any cracks in your home’s structure.

❒ Use natural pesticides to avoid any contamination.

Health Status Considerations

There are certainly several health factors that could cause a senior’s fall or accident at home, including the following:

- Hearing Loss: Even a mild degree of hearing loss could become a fall risk.

- Vertigo: This can make the elderly dizzy to the point where they can no longer balance properly.

- Vision Problems: Seniors should undergo yearly tests to ensure any eyeglass prescriptions are up to date.

- Medications: Certain types of medications can cause balance issues, dizziness or overall weakness.

- Strength: Ensure strength, mobility and balance are always in good shape.

- Foot Pain: Senior citizens experiencing pain or numbness in their feet could fall at home.

- Dehydration: Seniors need to stay hydrated all throughout the day.

- Vitamin D Deficiency: Low levels of vitamin D can result in reduced muscle strength and physical performance.

Lighting For Seniors

Sure. Here are some tips for lighting for seniors:

- Use bright, diffused light. Seniors’ eyes may not be as good as they used to be, so they need more light to see clearly. Diffused light is light that is scattered evenly, so it does not create harsh shadows.

- Avoid glare. Glare can be very uncomfortable for seniors and can make it difficult to see. Avoid using harsh overhead lights or lights that are aimed directly at the eyes.

- Use task lighting. Task lighting is light that is directed specifically at a task, such as reading or cooking. This can help seniors to see what they are doing more easily.

- Use dimmer switches. Dimmer switches allow you to adjust the level of light in a room. This can be helpful for seniors who may need more or less light depending on the time of day or their activity.

- Install nightlights. Nightlights can help seniors to see their way around at night without having to turn on bright overhead lights. This can help to prevent falls and accidents.

- Consider using LED lights. LED lights are a good option for seniors because they are energy-efficient and long-lasting. They also produce a bright, diffused light that is easy on the eyes.

Here are some additional tips for lighting for seniors:

- Consult with an occupational therapist or lighting designer to get personalized recommendations.

- Make sure the light switches are easy to reach and operate.

- Consider using motion-sensor lights in areas where seniors are likely to walk at night, such as the hallway and bathroom.

- Keep the light bulbs clean to ensure optimal brightness.

By following these tips, you can create a safe and comfortable lighting environment for seniors in their homes.

Home Safety Assessment For Seniors

If you are an older adult or have a loved one living on their own, a home safety assessment is a great way to find and eliminate any safety concerns. This assessment is typically performed by a licensed healthcare professional, including medical social workers or occupational therapists. The assessment may include things such as home improvement recommendations. Medical professionals may recommend installing handrails and extra lighting, for instance.

Since falls are one of the most common causes of injury among seniors, these assessments are a crucial preventative measure towards improving safety. One in four Americans age 65-plus fall every year, according to the National Council on Aging. Falls are the number one cause of injury-related deaths for seniors today.

Thinking about adding safety grab bars, a raised toilet seat or other modifications to prevent falls in your home? Our physical and occupational therapists provide free home safety screenings, and will make clinically guided fall prevention recommendations, as well as create a customized plan to fit your individual needs. We follow up with clinically guided installation of all of our fall prevention home safety products.

Our clinically guided solutions will ensure you and your loved ones can navigate your home environment safely and with confidence. Visit our Home Safety Solutions page to learn about the products and services we provide and install (we are licensed, bonded and insured), to help you prevent falls in your home.

Related Posts

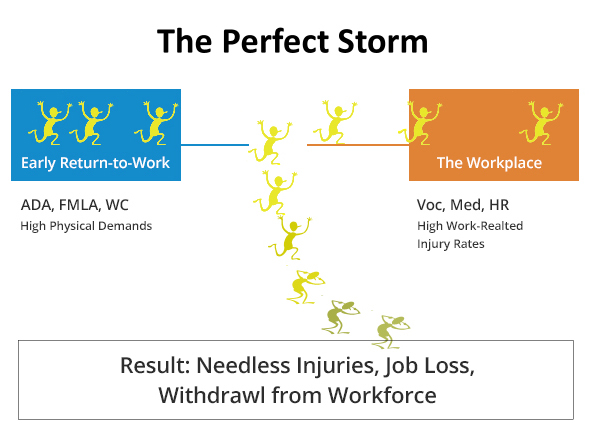

In Bob’s case, the damage was to the thoracic area, located in the middle of the spine. After surgery and extensive physical rehabilitation, he was declared maximum medically improved with permanent restrictions.

In Bob’s case, the damage was to the thoracic area, located in the middle of the spine. After surgery and extensive physical rehabilitation, he was declared maximum medically improved with permanent restrictions.